The salary trap: why hardly anyone gets paid overtime

by Katy Tynan

A few years ago during my final “real” job, I found myself sitting across the desk from a woman named Lisa. A recent graduate, we had hired her as a marketing and social media coordinator, and I was trying to explain that she needed to attend an event that night after work.

“Will I get paid for it?” she asked.

“No,” I said, “you’re a salaried employee: your work is not tied to hours, so sometimes you’ll have to work more than 40 hours per week.”

“OK,” she frowned, drawing absently on a piece of paper in front of her. “So I can take a day off later this week to make up for it?”

“No, it’s not about hours,” I said. “It’s about getting the job done, which includes this event. If you want to take time off, use your vacation time for that.”

The furrow between her brows was now so deep it was starting to remind me of the Grand Canyon. Honestly, I was having a pretty hard time with this conversation myself. The extra hours required of employees on salary just didn’t make sense. But there I was trying to justify the very policies I had always thought were one-sided in favor of employers. On the one hand, I was just doing my job: articulating the standard practices and expectations of the company I was hired to manage. On the other hand, I had asked the same questions myself and always felt the answer was unsatisfactory.

Why should a company be allowed to make employees work extra, for free?

In fact, it’s not supposed to be this way at all. It’s a result of old laws that haven’t been updated for years. It’s also one reason why so many working people today are less than enamored with their employers. There’s a reason you’re frustrated with your boss and your working hours, and it’s in something called the Fair Labor Standards Act.

When I was 16 I worked at a bed and breakfast down the street from my house. I washed dishes, made beds, cleaned bathrooms and did laundry. I learned how much starch to use on napkins, and why you shouldn’t try to cram two beds’ worth of sheets in one load of laundry. I also learned about getting paid. Every week I got a check with my hourly wage multiplied by the number of hours I worked, minus taxes. So unlike my friend with the furrowed brow, the more hours I worked, the more I made. That made sense.

But when I got my first job after college, I started getting paid a salary, and with my salary came benefits like paid time off and insurance. And this is where things started to get weird.

Back in 1938 when the industrial economy was booming, companies were getting away with paying workers low wages and having them work incredibly long hours. They were also using children as workers and paying them even less. That’s when the government stepped in and created the Fair Labor Standards Act (or FLSA). It created a federal minimum wage and the 40-hour work week. Under this standard, anyone who worked more than 40 hours in a single week had to be paid for those additional hours at one-and-a-half times their regular pay rate. It was meant to remove the incentive for companies to make a smaller number of employees work so hard that they made mistakes or got hurt.

However, legislators decided that not all jobs should be subject to this 40 hour standard. They made management jobs exempt from this provision. Any employee who is classified as “exempt” doesn’t have to be paid overtime no matter how many hours they work. It was designed to apply only to high-paying executive and management jobs – those with the decision making authority – since they were unlikely to try to work themselves into the ground.

You can probably see the problem here. In order to set a threshold for these high-level positions, the FLSA specified a weekly wage, above which workers could be considered exempt. When the law was first made in 1938, employees who earned under $30/week were supposed to be paid extra if they worked more than 40 hours, and those earning above $30/week were management and therefore exempt. They updated the pay levels in 1940 and 1975, but didn’t update them again until 2004. As of 2004, the magic executive-level salary is $455/week. This means if you’re a salaried employee making over $455 per week (about $24K/year), you generally won’t qualify for overtime pay. That’s remarkable, considering $24K/year is actually the federal poverty line for a family of four. Because the numbers haven’t been updated – or are kept artificially low – exemption from overtime pay (originally meant for high-level management jobs) eventually became the standard for nearly all salaried workers.

That’s a pretty big loophole.

It means that average white collar workers like Lisa can be asked to work more than 40 hours a week and the company doesn’t have to pay her anything extra.

In 1938, most jobs qualified for overtime pay. As recently as 1975, more than 65% of salaried employees were eligible for overtime because they weren’t considered “management,” or they didn’t make enough money to be exempted. But today a person only has to make about $24K/year and her company can make the case that they don’t have to pay her overtime. The result is that right now less than 8% of salaried employees earn overtime, and that number is continuing to drop.

Surely that doesn’t mean that companies would use a rule like this to make people work longer hours without paying them more, right? Let’s look at the numbers.

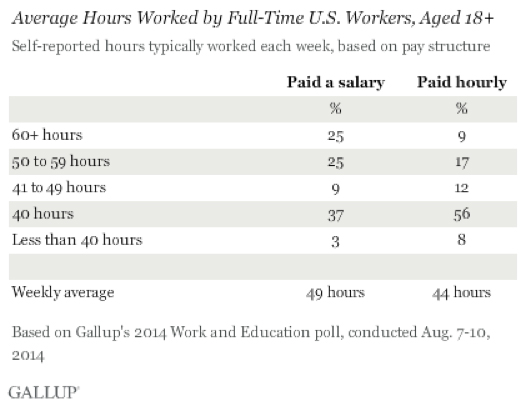

In a 2014 Gallup poll, 50% of salaried workers were working more than 50 hours per week, not because they wanted to but because their job required them to.

In a 2014 Gallup poll, 50% of salaried workers were working more than 50 hours per week, not because they wanted to but because their job required them to.

Unfortunately, two of the top five reasons people quit their jobs are too much unpaid overtime and lack of flexibility.

Like my lame attempt trying to explain to Lisa why she should have to come to an after-hours event and not get paid, yet use her vacation time if she takes a half day off to go to the doctor, there’s something fundamentally wrong with this situation. But because it’s been going on so long, we’ve developed a collective blind spot to it. We’ve come to believe as an entire working society that in order to receive benefits and paid time off, we have to give up more time than we’re paid for. We’ve bought into this pernicious idea that we owe our employers as many hours as it takes to “get the job done” despite the fact that in many cases our bosses just keep adding on to the workload.

In the era of “do more with less,” most people feel like their responsibilities are increasing every year but that their pay, and the time allocated to get all those things done, is not keeping up. Two-thirds of employees surveyed by Monster.com reported that their company does nothing to alleviate the stress created by their workload.

If employers have carte blanche to demand as much work and as many hours as they please, what can a person do to make a living and stay sane?

In some cases, employees are suing their employers. While salary is one of the factors that allows a company to exempt you from overtime pay, there are other factors such as whether you operate independently, what level of decision-making authority you have in the organization, etc. These are complicated topics for most employees, in fact the majority of workers have no idea that any of these standards apply. What they know is that if they are offered a salaried position, they probably won’t get paid more for working more. And while that has been great for companies, it’s making people take a hard look at how much of their time they are willing to sacrifice to hold down a “real” job.

For many this means shifting to working independently. One of the best ways to take back your schedule is to make your own, which is part of the reason we’ve been seeing a strong increase in people working for themselves.

So if you’ve been feeling like there’s something wrong with your relationship with the company you work for, you’re right. At least when it comes to overtime pay, it’s not you, it’s them. And while you can’t change the rulebook that has created the situation, you might be able to change how you choose to play the game.

FLSA rules are under review and there is a possibility that they will be updated later in 2015; more info here: http://www.wagehourinsights.

No comments yet.